|

We know the Pandemic can be challenging. Our Gift to You: A FREE E-Book. Click on link below to download our book in PDF format.

| |||

How the Pandemic has Affected Kids’ Mental Health: Voices of Parents and Professionals, and Urgent Actions Needed in Malaysia

8 Feb 2021, Dr Brendan J Gomez

Nearly 1-in-10 children were reported struggling with mental health issues even before the Covid pandemic struck Malaysia (National Health and Morbidity Survey, 2019). According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, children’s mental health emergencies have increased substantially in the United States over the course of the pandemic. In Malaysia, results from large-scale studies on the pandemic effect are yet to be released, if any. However, recent polls by UNICEF Malaysia indicate significant concerns. The biggest concern of 65% of young people polled was not knowing when things would return to normal. While in another poll, 70% of children say that the pandemic has made it more challenging to realize their dreams.

Azlina Kamal, the Education Specialist with UNICEF Malaysia says, the UN body views the pandemic as a health crisis which is quickly becoming a child rights crisis. “Through Voices of COVID Generation, students have expressed struggling with school closures, feeling depressed, and some explicitly mentioning suicidal tendencies” she said.

What can parents and the country do to reduce the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the emotional and mental health of children? According to Psychologist Dr Brendan J Gomez, the key in effectively addressing children’s psychological wellbeing and their developmental future is in identifying the risk-factors impacting children during this pandemic, identifying the protective-factors and resources we have in facing these challenges, and in sharing strategies in building resilience. These will go a long way in minimizing long-term effects on children and families.

How Social Changes are impacting Emotional Health

|

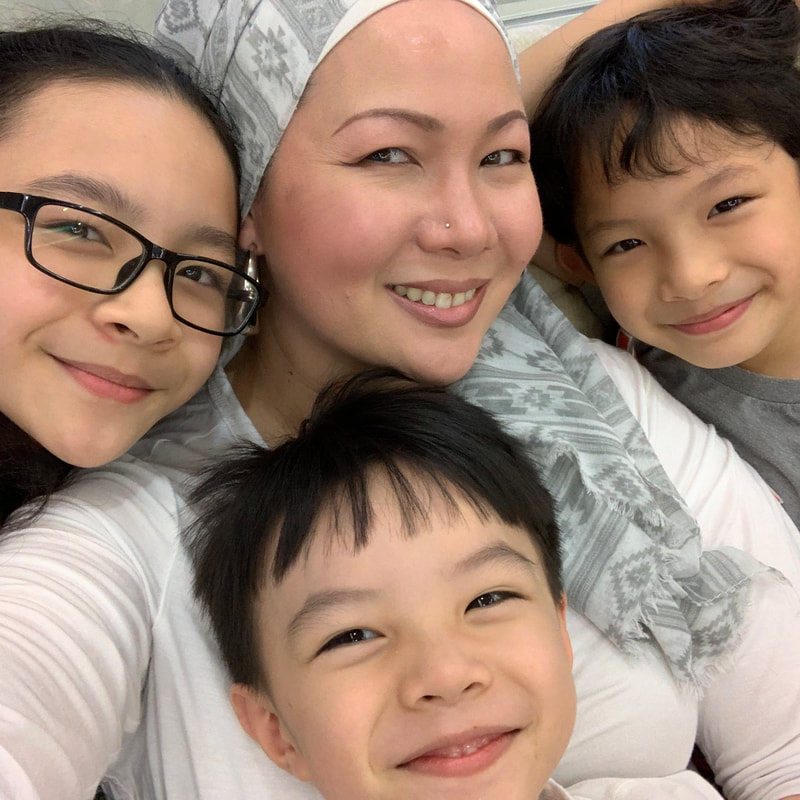

“Covid-19 has changed what normalcy means to children. The routines they had grown accustomed to, going to school, walking to the park, playing at the playground, spending time with friends, a birthday or festive celebration... these simple routines which are the hallmarks of childhood provide a sense of stability to kids as they grow up. But now, coming in and out of every lockdown, an MCO, CMCO, RMCO... it is all very unsettling to not know what to expect tomorrow, or the days after,” says Sheahnee Iman Lee, a Media Personality and Former News Anchor whose three kids are from 7 to 11 years old.

|

“I think the hardest challenge has been the uncertainty of when and where the next threat to our survival is going to come from. Both children and parents are worried for their future, of how long they will be confined to their homes and imprisoned in their fears, and how often this imprisonment will repeat itself in the coming months,” says Dr Brendan, who works with families and organizations.

“This ‘oppression of freedom’ is what I think is hard on children,” says Diana Zin Zawawi who has three children ages 5 to 10, and is in the Civil Service.

“If adults are struggling to come to terms with that, what more our children, where their cognitive abilities are yet to be fully developed to make sense of all this. Thus, this challenging and stressful period of adjusting and adapting have affected children in more ways than we realize,” says Kelvin Chee and Luisa Yeng whose three children are from 7 to 14 years of age.

“There is no doubt that change of routines and the lack of contact with friends and loved ones has caused an emotional upheaval in them. They have fears of the unknown - will they ever see their friends again, and will life be normal again?” says Carol Joseph a mother of girls aged 10 and 11 who works as Director of Operations in the Klang Valley.

“With the children that I work with (as a therapist), there is a spike in anxiety and behavioural problems during this period of time. Some are defiant, many feel demotivated and helpless as they do not have their normal routines or outlets for coping. It’s often picked up as a behavioural problem of not attending classes, incomplete work or having high conflict at home with family members. There is also the worrying ones who withdraw and quietly bottle up all their frustrations and emotions, not knowing where or how to express it or thinking that no one understands them.” says Siew Ju Li, a play therapist with 3 kids of her own aged 6 to 10.

Azlina Kamal adds that a lack of support (from friends, family and community), lack of access to services and opportunities, and lack of money were key risk-factors children were facing in this pandemic.

“Most of my students, especially from families hard-hit financially, expressed losing their concentration, being easily distracted, and not being able to motivate themselves to focus or study. They feel like giving up on their studies. Physically, mentally, and emotionally, they tend to switch off and some have even taken 'off days' from social media during the lockdown. Some of my students have stopped attending my online lessons. Some are too tired and some have interrupted sleep cycles. As a result, they are unable to keep up with lessons or improve as much as they hope.” says Caleb Ho who provides private tuition to students aged 13 to 18 years old.

“Generally, they are feeling bored, frustrated, perhaps angry due to the isolation and the uncertain times. However, there are children who are affected more severely, especially from the lower income groups where parents are trying to make ends meet, which may result in intense fear of not knowing when the next meal will be.” says Kelvin Chee.

“This ‘oppression of freedom’ is what I think is hard on children,” says Diana Zin Zawawi who has three children ages 5 to 10, and is in the Civil Service.

“If adults are struggling to come to terms with that, what more our children, where their cognitive abilities are yet to be fully developed to make sense of all this. Thus, this challenging and stressful period of adjusting and adapting have affected children in more ways than we realize,” says Kelvin Chee and Luisa Yeng whose three children are from 7 to 14 years of age.

“There is no doubt that change of routines and the lack of contact with friends and loved ones has caused an emotional upheaval in them. They have fears of the unknown - will they ever see their friends again, and will life be normal again?” says Carol Joseph a mother of girls aged 10 and 11 who works as Director of Operations in the Klang Valley.

“With the children that I work with (as a therapist), there is a spike in anxiety and behavioural problems during this period of time. Some are defiant, many feel demotivated and helpless as they do not have their normal routines or outlets for coping. It’s often picked up as a behavioural problem of not attending classes, incomplete work or having high conflict at home with family members. There is also the worrying ones who withdraw and quietly bottle up all their frustrations and emotions, not knowing where or how to express it or thinking that no one understands them.” says Siew Ju Li, a play therapist with 3 kids of her own aged 6 to 10.

Azlina Kamal adds that a lack of support (from friends, family and community), lack of access to services and opportunities, and lack of money were key risk-factors children were facing in this pandemic.

“Most of my students, especially from families hard-hit financially, expressed losing their concentration, being easily distracted, and not being able to motivate themselves to focus or study. They feel like giving up on their studies. Physically, mentally, and emotionally, they tend to switch off and some have even taken 'off days' from social media during the lockdown. Some of my students have stopped attending my online lessons. Some are too tired and some have interrupted sleep cycles. As a result, they are unable to keep up with lessons or improve as much as they hope.” says Caleb Ho who provides private tuition to students aged 13 to 18 years old.

“Generally, they are feeling bored, frustrated, perhaps angry due to the isolation and the uncertain times. However, there are children who are affected more severely, especially from the lower income groups where parents are trying to make ends meet, which may result in intense fear of not knowing when the next meal will be.” says Kelvin Chee.

The Online Life of Children and Its Challenges

“For many poorer children, there is a feeling of hopelessness in virtual learning due to the lack of online devices or Wi-Fi at home.” says Kelvin. A study conducted by The Ministry of Education involving 670,000 parents and 900,000 students found that about one-third of children in both urban and rural areas do not own any devices.

“This creates a disparity between the rich and the poor in education accessibility, thus affecting both academics and how poorer children see themselves (as they compare with the ones who have access to online education). At the same time, there are also developmental challenges for online schooling – even for those who have access,” says Dr Brendan.

“This creates a disparity between the rich and the poor in education accessibility, thus affecting both academics and how poorer children see themselves (as they compare with the ones who have access to online education). At the same time, there are also developmental challenges for online schooling – even for those who have access,” says Dr Brendan.

|

“Not only is online-schooling tough on children because of their short attention-span, but they find it tough to participate in class and engage with other children during discussions; while realizing that they are not going to be able to see and play with their friends like how they could pre-pandemic,” says Diana Zin.

|

“My middle child has focus and attention deficit issues with learning online. And, being at home with three kids where all are learning online at the same time, it can be pretty raucous. If I am not sitting right next to him at all times, he’s off doing something else and there’s nothing his teacher can do about it. I have my own deadlines to meet too and it can be pretty difficult not to lose my cool,” says Sheahnee Iman.

“At the same time, the hours spent on screen is not doing them good as it tires them out, “ says Diana Zin.

“At the same time, the hours spent on screen is not doing them good as it tires them out, “ says Diana Zin.

“The high use of electronics and screen time during the pandemic brings with it a whole new set of behaviours. A preference and even addiction to playing games online and obviously conflict when I confront my child over these long hours. It is draining having to find ways to pry your child away from the screen,” says Swanee Teh, a pharmacist with two children 11 and 13 years of age. “The pandemic has robbed them of play time and physical interaction which I feel limits their friendships. This has led to feelings of loneliness and feeling down. Not being able to go to school also means lesser sporting activities and fewer avenues to expand pent up energy to boost happiness,” says Swanee.

“There are also risks to children in being online, especially when unsupervised; and this includes online sexual abuse, cyberbullying, risk-taking online behaviour, potential harmful content, and where there is risks to a child’s privacy, “says Azlina Kamal.

“There are also risks to children in being online, especially when unsupervised; and this includes online sexual abuse, cyberbullying, risk-taking online behaviour, potential harmful content, and where there is risks to a child’s privacy, “says Azlina Kamal.

What parents can do to help their kids

(and themselves)

(and themselves)

|

“How we react to change will determine how our kids cope with it,” says Dr Brendan, who says that many parents are doing their best to keep their children happy. “True, there are risk-factors for psychological long-term effects from this pandemic, but there are equally protective-factors that we as parents can use to build resilient kids,” he adds.

|

“MCO 2.0 came like a truck out of nowhere and caught us by surprise as we thought we were on the road to recovery,” shares Kelvin and Luisa. “We noticed that our son who is normally bubbly and easy-going was showing signs of being sad and demotivated, especially during those days where both of us parents had to work and could not give him the full attention to create fun experiences together. Those were the days where he felt like there was nothing to look forward to except schoolwork and house chores,” says Luisa. “So, to alleviate this condition, we were intentional to add in some variety to our days. We sometimes added surprises like getting ice-cream in the middle of the day, allowed for sleepovers during weekends in our room, movie nights, building DIY projects, catching caterpillars to observe the metamorphosis, learning new skills like cycling, and skateboarding.”

“I think it is important to keep engaging with children intellectually, emotionally and spiritually during this challenging time,” says Diana Zin. “I always encourage them to be active even in the house, sometimes doing random dance when we listen to music, and keep them occupied with other fun activities like drawing, or doing LEGOs. My daughter enjoy baking now, too. Our kids need to know that no matter the unforeseen changes in life, that they can adapt and make the most of it.”

Carol Joseph emphasizes how we need to take a balanced approach and address their mind, their body and their soul or spirit. “My children went through a pretty hard time as they lost their grandmother during the pandemic. My eldest who was very close to her grandma, also faced pressure in school on academic performance.” “To start with, parents need to be vigilant in spending more time with their children no matter how tired they are. Build stronger connections through talks, play etc. Plan routines. Keep them active by scheduling exercise or family dance time. Encourage them to connect with some friends of their same age group. And most importantly build a sense of purpose in them. Especially the pre-teenagers and teenagers who are the stage of discovering and building their own personality.”

“I think it is important to keep engaging with children intellectually, emotionally and spiritually during this challenging time,” says Diana Zin. “I always encourage them to be active even in the house, sometimes doing random dance when we listen to music, and keep them occupied with other fun activities like drawing, or doing LEGOs. My daughter enjoy baking now, too. Our kids need to know that no matter the unforeseen changes in life, that they can adapt and make the most of it.”

Carol Joseph emphasizes how we need to take a balanced approach and address their mind, their body and their soul or spirit. “My children went through a pretty hard time as they lost their grandmother during the pandemic. My eldest who was very close to her grandma, also faced pressure in school on academic performance.” “To start with, parents need to be vigilant in spending more time with their children no matter how tired they are. Build stronger connections through talks, play etc. Plan routines. Keep them active by scheduling exercise or family dance time. Encourage them to connect with some friends of their same age group. And most importantly build a sense of purpose in them. Especially the pre-teenagers and teenagers who are the stage of discovering and building their own personality.”

Sheahnee believes parents need to be in a good space emotionally and psychologically first. Having to be our kids’ home tutors, personal chefs and doctors while meeting our own work deadlines from home is bound to result in added stress for any parent. “So I believe the key is for parents to structure our own routines first,” says Sheahnee. “Set aside time for kids and time for your own work; and time where kids can feel free to come and speak to you. Workout a daily timetable. Spousal support is crucial too. When one parent is in a video conference, the other parent should ideally not be in one too. Easier said than done, I know, but hopefully employers can take this into account.”

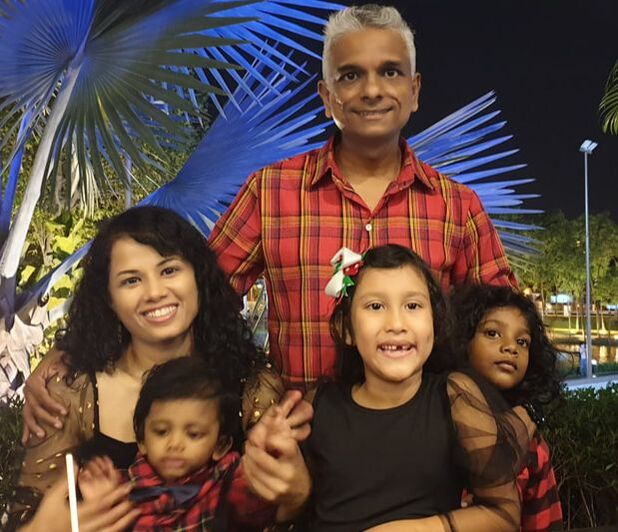

“Parental exhaustion is indescribable! The pandemic fatigue on us in real as we juggle careers, parental duties, manage online home-schooling (for young children), and govern the household all at one go EVERY SINGLE DAY,” says Angeline Rose and Brian Pereira, who work as an entrepreneur and CFO respectively, and have three kids aged 21 months to 6 years of age. “It’s debilitating, depriving, maniacal, unforgiving and incredibly taxing on our emotional health, spirits and mind, to be very honest. We don’t have time for ourselves any longer and as soon as evening sets in, all we can think about is hurrying to tuck the kids into bed just so we can exhale the leftover hours of the day before a new dawn approaches,” says Angeline, who half-jokingly says that she can add this to a thriller book if she writes one. “

|

For Brian and me, a time-out eases the rabbet of these burdens. We need to let go and let out as much as we can so as not to gather an inner furnace that could potentially sabotage the relationship with our children (emotionally). Building positive resilience to this requires an avenue to letting off steam, so we usually plan a very small adults-only get-together every fortnight/month and indulge in absolutely exciting game nights and foods that make the whole bizarre ‘living in the greatest pandemic age’ that much more survivable.”

|

Understanding the struggles parents are going through, Dr Brendan Gomez applauds many who are working hard in juggling family wellbeing, work and finances. “At the same time, parents need to feel comfortable reaching out to psychologists for help when they need to, and to learn how to identify early warning signs of emotional distress in their children and themselves. There is no shame in asking for help. We all need to,” says Dr Brendan.

|

Swanee shares how she invested in four areas so as to help her and her children cope better emotionally. “One, I took up a parenting course. I realise that I cannot change other people, I can only change myself. So I took up a course on how to better communicate with my children (and spouse). Two, we created activities as a family, both outdoors and indoors, i.e. cycling and playing board games, preparing meals together and watching TV together. Three, as a pharmacist and natural therapies advocate, I use certain natural therapies to help my family cope better with emotional stress. And four, I learned more about spiritual support.”

|

What we as a nation can do to better support kids’ mental health

“The crisis is putting young lives at risk in key areas that include education, food, safety and health of children. As the crisis deepens, family stress-levels also are rising. Thus, access to psychosocial support is critical,” says Azlina Kamal of UNICEF.

“Children and teens need social interactions for healthy physical and psychological development. As humans, we thrive on human interactions. The biggest blow to our development as a species has been how Covid has divided and conquered – keeping everyone at distance from each other, and attacking the fundamentals of what makes us human,” says Dr Brendan. He adds that there are also key developmental steps that children are missing out on due to curbs on their social environment – from academic mile stones to achievement events such as sports, to friendships and relationships which help promote self-esteem, confidence, and social support. Dr Brendan shares how psychosocial support in the form of wellbeing support groups for parents and for children, and emotional intelligence workshops for parents, teens, and organizations are key in building community-wide resilience and in improving the wellbeing of the nation. While he is already doing this, he says the country urgently needs more trained psychologists employed in schools, workplaces, community and religious centres to be able to address the long-term effects of the pandemic on the mental wellbeing of the country. The National Association of School Psychologists in the US recommends a ratio of 500 students to one school psychologist. “There’s going to be a lot of people suffering – both children and parents. And we just don’t have enough trained people, and enough employable positions created in Malaysia,” says Dr Brendan.

“The new norm is already tough as it is. What we need to do is practice #kitajagakita to a whole different level. All key players have to work together and cooperate to build a conducive environment for children to be able to adapt to this new situation. This includes parents, government, education institutions and involved parties,” says Diana Zin.

“Children and teens need social interactions for healthy physical and psychological development. As humans, we thrive on human interactions. The biggest blow to our development as a species has been how Covid has divided and conquered – keeping everyone at distance from each other, and attacking the fundamentals of what makes us human,” says Dr Brendan. He adds that there are also key developmental steps that children are missing out on due to curbs on their social environment – from academic mile stones to achievement events such as sports, to friendships and relationships which help promote self-esteem, confidence, and social support. Dr Brendan shares how psychosocial support in the form of wellbeing support groups for parents and for children, and emotional intelligence workshops for parents, teens, and organizations are key in building community-wide resilience and in improving the wellbeing of the nation. While he is already doing this, he says the country urgently needs more trained psychologists employed in schools, workplaces, community and religious centres to be able to address the long-term effects of the pandemic on the mental wellbeing of the country. The National Association of School Psychologists in the US recommends a ratio of 500 students to one school psychologist. “There’s going to be a lot of people suffering – both children and parents. And we just don’t have enough trained people, and enough employable positions created in Malaysia,” says Dr Brendan.

“The new norm is already tough as it is. What we need to do is practice #kitajagakita to a whole different level. All key players have to work together and cooperate to build a conducive environment for children to be able to adapt to this new situation. This includes parents, government, education institutions and involved parties,” says Diana Zin.

|

Luisa quotes the saying "It takes a village to raise a child". To do this, Kelvin says that we should focus on increasing mental health education, up-skilling teachers to make online learning engaging and fun, working with NGO and religious bodies to provide community support systems, and providing incentives for companies to send their employees to parenting courses so they can be better equipped to raise their families during this pandemic. “When a family is happy and strong, it will reflect in the work performance and impact work productivity,” says Luisa.

|

“And companies need to give parents a break! Nothing is normal anymore. Recognise that you won’t get the same results at the same speed. We are struggling too. Less pressure from employers will definitely go a long way to reducing stress levels at home,” says Sheahnee.

“It was firstly financial worries that struck me as a parent,” says Swanee. “If parents are able to continue to earn an income, a big chunk of financial worries will be abated. Couple that with doing things within our control to feel better such as equipping people with know-how on coping with mental stress, I believe that we will be able to fare better and be more resilient than before,” says Swanee.

“The government has a lot to do in leading and implementing measures that support mental health of not just kids but adults as well. We can certainly take a leaf out of Japanese society and learn to be more polite, helpful, and cooperative,” says Caleb Ho.

According to UNICEF, there is also a need to look at the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable groups, and design proper policy responses to ensure that no one is left behind, especially given the absence of a strong social protection system. “What worries me is when illness, poverty, inequality, and food insecurity can add to the mental health challenges children face in the country,” says Azlina. Urban low-income families are much more likely to be unemployed, have cut working hours and experience greater challenges in accessing healthcare and home-based learning, according to UNICEF.

“As a nation, we need to support each other in every way possible. Understand that for each person, the situation is vastly different. One family may be struggling with only one computer between both parents and several kids. Another family may not know when their next meal will be,” says Sheahnee. She adds that in education, not to expect school results to be the same. “Don’t hold kids to the same academic standards as you would pre-pandemic. Pause all examinations, please. Understand that learning and performing online is mentally exhausting and kids no longer have the same outlets to let off steam.”

“I think that many times when we talk about children, it is about their academics, and enrichment activities for a better future. Those are important. It’s also important to consciously support their emotional well-being. Helping children to understand and express their emotions, providing them with strategies and skills needed to cope, and helping them accept that this pandemic is difficult will all be important,” says Ju Li.

“It was firstly financial worries that struck me as a parent,” says Swanee. “If parents are able to continue to earn an income, a big chunk of financial worries will be abated. Couple that with doing things within our control to feel better such as equipping people with know-how on coping with mental stress, I believe that we will be able to fare better and be more resilient than before,” says Swanee.

“The government has a lot to do in leading and implementing measures that support mental health of not just kids but adults as well. We can certainly take a leaf out of Japanese society and learn to be more polite, helpful, and cooperative,” says Caleb Ho.

According to UNICEF, there is also a need to look at the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable groups, and design proper policy responses to ensure that no one is left behind, especially given the absence of a strong social protection system. “What worries me is when illness, poverty, inequality, and food insecurity can add to the mental health challenges children face in the country,” says Azlina. Urban low-income families are much more likely to be unemployed, have cut working hours and experience greater challenges in accessing healthcare and home-based learning, according to UNICEF.

“As a nation, we need to support each other in every way possible. Understand that for each person, the situation is vastly different. One family may be struggling with only one computer between both parents and several kids. Another family may not know when their next meal will be,” says Sheahnee. She adds that in education, not to expect school results to be the same. “Don’t hold kids to the same academic standards as you would pre-pandemic. Pause all examinations, please. Understand that learning and performing online is mentally exhausting and kids no longer have the same outlets to let off steam.”

“I think that many times when we talk about children, it is about their academics, and enrichment activities for a better future. Those are important. It’s also important to consciously support their emotional well-being. Helping children to understand and express their emotions, providing them with strategies and skills needed to cope, and helping them accept that this pandemic is difficult will all be important,” says Ju Li.

|

Carol says “During the course of this pandemic, I realised that in Malaysia, we do not have any channel or platform for teens to come together to find friends with common interest, a place where they are comfortable to express themselves. A place where they are not afraid to be themselves and do not have the fear of being judged. A place where they have proper mentors to guide them and discover things that are bigger than themselves. To take it further, to build a sense of higher purpose in their lives. If we don't do this, their mentors and point of reference will be their idols on TIK TOK and YouTubers.”

|

“I think that our community or even our neighbourhoods can organise activities for children to participate in,” says Swanee. “If we are able to create activities that involve children, that empower them, that allows them to express themselves without fear of being judged, perhaps we will be able to see that we are not alone in this. And, that while it is tough, it’s going to be ok. Perhaps to create a collage of videos of different children saying something to another child who is under the pandemic. By this, they will realise that they are not alone in the way they are feeling. Overall, to create a more positive environment that we are in this storm together and to spread hope that brighter days will be ahead.”

END

END